by Ben Crisford, Assistant Forest Manager in South West Scotland

In part 1 of this blog, we followed the journey of some trees. From their humble beginnings, as seedlings in one of the UK’s specialist forest nurseries, we followed them all the way through to their eventual establishment in the forest. Along the way, I introduced some of the many crucial but little-known jobs that professional forest managers carry out to help those seedlings reach their best potential.

When we left our trees at the end of Part 1, they were pretty much fending for themselves. No longer threatened by competition from weeds and browsing by deer. This is a point at which the forest goes quiet, and the job of the forester (for a while, at least) becomes a little less hands-on and a little more cerebral.

Figure 1: Drone photo showing ‘mid-rotation crops’ of Sitka Spruce.

When deciding what to ‘do’ with a forest and its trees, there are so many potential constraints and opportunities to consider that it would be impractical to list them all here. Some of these (such as the need to match tree species to site conditions and adhere to the UK Forestry Standard) apply everywhere and are obvious to the forester, but other, more site-specific constraints are maybe less so.

For this reason, many stakeholders who have a direct or indirect interest in the forest are invited to have input into the management planning process, including (but not limited to) archaeologists, ornithologists, neighbours, local wildlife groups and local authorities. All are included where appropriate.

The synthesis of these responses, along with the careful silvicultural decisions and overarching legal requirements, eventually decides the fate of the trees that were planted in part 1 and ensures that their future management is responsible and sustainable. This plan is then presented to a Woodland Officer (from one of the devolved government regulators), who has significant input into the process and assesses our proposals against the UK Forestry Standard.

The job of a Woodland Officer is not an easy one. An extremely diverse range of applications cross their desks, so a breadth of forestry knowledge is needed. Throw in all the challenges of administering the labyrinthine forestry grants system (and guiding foresters through it), and you get some idea of how demanding a role this could be. Forest Managers and Woodland Officers are not always in agreement, but there is a mutual respect.

Once a plan is approved and in place, the first major intervention that the trees are likely to experience is a thinning, where a proportion of the planted trees are felled at a relatively young age. The aim of this is to improve the growth and ‘form’ of the trees that are retained, and whilst this can offer great benefits, it is a complex and potentially risky operation and isn’t appropriate for all sites.

Nowadays, thinning is most often carried out by machines, operated by a specialist subset of harvester and forwarder operators (already highly skilled professions in their own right), which adds its own set of challenges.

Navigating heavy machinery through a crop of trees (planted at a spacing of 2m x 2m) takes a steady hand, an experienced eye, and a carefully considered approach. These operators are counted upon not to cause damage to standing trees, or excessive ground disturbance – which is a tall order on challenging sites but is crucially important.

Figure 2: 2nd Rotation thinning of imporved Sitka Spruce.

After thinnings (or not, on exposed sites), it’s time once again to watch the trees grow, and wait for them to reach maturity.

When foresters refer to maturity, they generally mean the point at which a tree’s growth rate begins to slow down (between 50 and 70 years old for Sitka spruce), and in an ideal world, felling would coincide with this point. However, our maritime climate has other ideas, and often blows them over before they get there. For this reason, we tend to harvest trees when they’re a little smaller, and a rotation length of around 40 years is fairly typical in upland Britain.

So around 40 years (give or take) after the trees left the nursery in part 1, it is time for them to be harvested, and to enjoy a second life as wood products in industry or in our homes.

These ‘clearfell’ operations carry with them a sudden land-use change, and it’s important not to understate the impact they can have, particularly visually. I think it’s also true however, that these operations are often unfairly portrayed and misconceived, and many criticisms landed at them are not well founded.

In terms of biodiversity, felled sites and young replanting sites are not the wastelands that some perceive them to be. In fact, they are one of the numerous ecological niches provided by commercial forestry, and a great number of species welcome the disturbance that felling creates. The rotational nature of forestry helps to ensure that the animals who preferred the mature trees are still catered for in the locality, and pre-operational surveys minimise the risk of any protected species being rudely disturbed by our work.

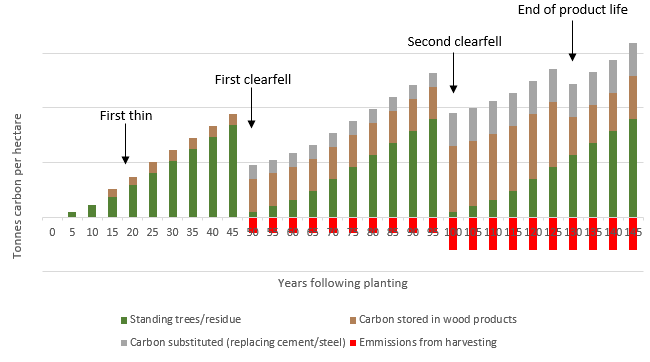

In terms of the impact on the wider environment, the use of wood products resulting from sustainably harvested forests is overwhelmingly positive. A common misconception is that native woodlands draw down more atmospheric carbon than commercial coniferous forests, but in fact the opposite is true (due to the faster growth of conifers and the carbon storage in resultant wood products). That is not to say that we do not need native woodlands (their ecological richness absolutely cannot be replaced by conifer plantations), just that both have an important part to play.

Figure 3: Visual representation of carbon sequestration, storage, and substitution in commercial forests. Intended as a visual guide only, it is not based on empirical data.

Final crop harvesting is largely carried out by harvesters and forwarders, ‘go anywhere’ machines that – to the uninitiated – may appear to mow down forests in a fairly gung-ho fashion. In fact, a methodical and well-planned approach is essential.

Despite generous ground clearance, soft ground and remnant deep ploughing present challenges to these machines, and they rely on a solid mat of ‘brash’ (collected from the waste branches of felled trees) to support their weight. Steep ground too creates difficulties, and sometimes (where no safer alternative exists) operators rely on the assistance of specialist chainsaw operators and/or mechanical winch systems.

Many may also not realise, that the machine operators’ remit extends far beyond the felling of trees and extracting to roadside. It is the harvester driver who decides (based on size and form) which products can be cut from each tree, and cross cuts the stem into a range of different lengths. In turn, it is the forwarders’ job to recognise these (often subtly different) lengths of wood left in the harvesters’ wake, and sort them into safe and accessible stacks at the side of the road.

Figure 4: Forwarder taking cut timber to roadside.

To discuss all the other essential workers in the supply chain who deserve of a mention would make this (already long) article considerably longer, so it is far from exhaustive.

Among those notably absent are the timber wagon drivers who tackle challenging road conditions daily, the fitters who service harvesting machines in extremely remote environments, and mensuration practitioners whose uncomfortable job it is to navigate on foot through dense crops to calculate how much timber is there.

Despite not being comprehensive, this article should give some indication of the breadth of roles that are created by commercial forestry and the number of skilled workers there are who fulfil them. In addition, it should highlight the demanding role of the Harvesting Managers across the country (including Tilhill’s own harvesting team), whose role is to tie all these moving parts together and ensure the sawmills and their workers can keep moving – this is no small feat.

Figure 5: Forest Manager and Harvesting Manager site visit.

I would like to finish by acknowledging that the reality is of course more complex than my blogs would suggest. At any one time in a busy forest, multiple operations described in these articles will be happening simultaneously. For that reason, when people from outside the industry ask what a forester does, it is not an easy question to answer. The full answer is so very long.

Forestry is an industry that suffers from very limited public awareness. Many of the operations happening in the forest are hidden from view, and when they are visible, the months and years of careful planning that has gone on behind the scenes is not. This lack of awareness and important perspective all too often leads to misconceptions, and that is something we need to work together as an industry to tackle. The need for more accessible written content is clear, and these blogs have been my contribution.

Author’s note to the Tilhill Harvesting team: I hope you don’t object to me writing an article largely about harvesting, despite my forest manager credentials; I think I made it flattering enough that you won’t mind.

Missed Part 1 of Ben's Blog?

Read in full here:

Find out moreView Upcoming Graduate Programme